I do think that sexism is the primary force that has generated and maintained most of the negative narratives about Hillary.

Of course accusations of sexism always bump up against several serious impediments:

1) Almost nobody will admit to it. Conservatives decided long ago that all such accusations (sexism, racism, homophobia, etc.) are standard liberal baloney whose only real intent is to shut down debate, and liberals tend to possess a sense of moral entitlement which leads them to consider themselves automatically exempt from all such accusations. (Side note: if you did roll your eyes above, there’s a good chance I’m describing you here. Sorry.)

2) Overt sexism is significantly more likely to be tolerated in our society than overt racism. It is a low-risk form of bigotry and discrimination that rarely damages professional or political careers. Because of this, far fewer people worry about crossing that line.

3) We have formed a sort of collective blindness to sexism that allows us to pretend that we are on top of the issue while simultaneously ignoring the many ways in which it actually permeates our society. (There’s a reason it’s called a “glass” ceiling.)

4) Unlike men, women who make demands are still often seen as unfeminine and inappropriately aggressive, bordering on deviant. And if the people most aggressively pushing against the glass ceiling are “broken” or “deviant”, it’s easier to justify dismissing both them and their concerns.

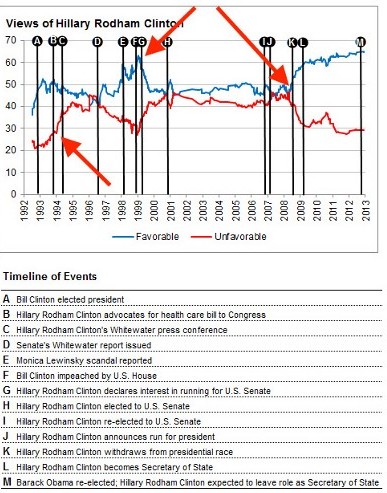

So I’ve made a claim. Let’s look at some numbers. Take a look at the image above. It was put together by Nate Silver, who based it on over 500 high-quality phone surveys dating back to the early 90’s. If we take a look at the polling data, very obvious patterns emerge.

In the early 90’s her polling was great, which was typical for an incoming First Lady. But Hillary had no interest in being a typical First Lady, and soon took charge of one of the most important policy initiatives of the Clinton Presidency: Universal Health Care. If you look at the first large red arrow I have on the graphic, you’ll see that as soon as she did that her negatives skyrocketed. And yes this was before Whitewater. In fact during the ongoing Whitewater investigations her polling improved dramatically, so she actually became significantly MORE popular during that period, not less.

Now take a look at the second arrow. This is where she declared that she was going to run for the Senate. See what happened? She was at one of the most popular periods of her life, but as soon as she declared a run for the Senate her favorables plummeted while her unfavorables rose sharply. Then once she was elected, her scores stabilized and even improved. Now look at the third arrow. Nearly exactly at the same time she withdrew from the Presidential race her favorables took off again, rising to levels that many considered remarkable. (Or are we pretending not to remember that until very recently Hillary was one of the most popular politicians in the country?) In fact the image on the left of the graph is part of the “bad-ass Hillary” meme that started during this time. And her polling stayed high right up until she decided to run for President again. Her numbers since then are not on this particular graph, but I think we all know what happened to them.

So what do we see in this data? What I see is that the public view of Hillary Clinton does not seem to be correlated to “scandals” or issues of character or whether she murdered Vince Foster. No, the one thing that seems to most negatively and consistently affect public perception of Hillary is any attempt by her to seek power. Once she actually has that power her polls go up again. But whenever she asks for it her numbers drop like a manhole cover.

And in fact I started thinking more about this after reading an article that Sady Doyle wrote for Quartz back in February. The title of the piece was, “America loves women like Hillary Clinton — as long as they’re not asking for a promotion.” In the article Ms. Doyle asserted that, “The wild difference between the way we talk about Clinton when she campaigns and the way we talk about her when she’s in office can’t be explained as ordinary political mud-slinging. Rather, the predictable swings of public opinion reveal Americans’ continued prejudice against women caught in the act of asking for power…”

And yes this is the kind of statement that many people will find reflexively annoying. But that doesn’t make it any less true, and the data certainly seems to support it. Even NBC news, looking back over decades of their own polls, stated that, “she’s struggled to stay popular when she’s on the campaign trail.” If this has nothing to do with gender, then wouldn’t the same thing happen to men when they campaign? But it doesn’t.